Righthanded gesturing in apes hints at the origins of human language The origins of language have long been a mystery, but mounting evidence hints that our unique linguistic abilities could have evolved from gestural communication in our ancestors. Such gesturing may also explain why most people are righthanded. Researchers at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center recently ex amined captive chimpanzees and found that most of them predominantly used their right hand when communicating with one another—for example, when greeting another chimp by extending an arm. The animals did not show this hand preference for noncommunicative actions, such as wiping their noses. Such lateralized hand use suggests that chimpanzees have a system in their left brain hemisphere that is coupled to the production of communicative gestures, says study author William Hopkins. The same cerebral hemisphere is host to most language functions in humans, which hints that an ancestral gestural system could have been the precursor for language, he says. That notion is supported by previous studies that have shown anatomical asymmetries in chimpanzees’ brains in areas that are considered to be ho mologues of human language centers, such as Broca’s area, Hopkins says. “Chimps that gesture with their right hand typically have a larger left Broca’s area, and those that don’t show a [hand] bias typically don’t show any asymmetry in the brain,” he notes. The idea that language emerged from an ancestral gestural system located in the left brain hemisphere could explain why the vast majority of people are righthanded, Hopkins says. If gesturing was strongly selected for in human evolution, then the fact that most people are righthanded is a consequence of that. This hypothesis challenges the longheld view that the opposite scenario is true: that righthandedness emerged for motor skills such as tool use and that communication built on the developed asymmetry in the motor system later.

Source of Information : Scientific American Mind March-April 2010

Saturday, July 31, 2010

Friday, July 30, 2010

Gene Target Beats Oil Remedy

Therapy shows promise in a deadly degenerative brain disease

The 1992 tearjerker Lorenzo’s Oil told the true story of one family’s struggle to save their son from Xlinked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a deadly degenerative brain disease. Unfortunately, over the ensuing years, the oil of the fi lm’s title, a dietary supplement, has not panned out as the cure many people hoped it would be. Now a paper in the November 2009 issue of Science suggests that the longsought cure may come from gene therapy—a famously hyped approach to treatment that tragically caused the death of a teenage experimental subject in 1999. Since then, however, researchers have continued to cautiously pursue gene therapy for certain disorders with known genetic origins. ALD, for instance, is caused by mutations in a gene called ABCD1, leading to unusually high levels of a type of fatty acid that damages the material insulating some neurons. It affects about one in 20,000 sixto eight year old boys, leading to death before adolescence. The main treatment is still bone marrow transplantation: a risky procedure that relies on finding a suitable donor, explains Patrick Aubourg, a neurologist at France’s INSERM research institute. Now Aubourg and his team have showed in a preliminary trial that gene therapy stopped ALD in two boys for whom they could not fi nd matching bone marrow donors. After fi shing stem cells from each individual’s own blood, the researchers inserted a normal version of the ABCD1 gene into some of the cells and transplanted them back into the kids. The results were promising: ALD progression halted within 14 to 16 months. A year later neither child had further brain damage or leukemia (a side effect in some past gene therapy trials). The researchers have now treated a third individual and are preparing for larger trials in Europe and the U.S.

Source of Information : Scientific American Mind March-April 2010

The 1992 tearjerker Lorenzo’s Oil told the true story of one family’s struggle to save their son from Xlinked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a deadly degenerative brain disease. Unfortunately, over the ensuing years, the oil of the fi lm’s title, a dietary supplement, has not panned out as the cure many people hoped it would be. Now a paper in the November 2009 issue of Science suggests that the longsought cure may come from gene therapy—a famously hyped approach to treatment that tragically caused the death of a teenage experimental subject in 1999. Since then, however, researchers have continued to cautiously pursue gene therapy for certain disorders with known genetic origins. ALD, for instance, is caused by mutations in a gene called ABCD1, leading to unusually high levels of a type of fatty acid that damages the material insulating some neurons. It affects about one in 20,000 sixto eight year old boys, leading to death before adolescence. The main treatment is still bone marrow transplantation: a risky procedure that relies on finding a suitable donor, explains Patrick Aubourg, a neurologist at France’s INSERM research institute. Now Aubourg and his team have showed in a preliminary trial that gene therapy stopped ALD in two boys for whom they could not fi nd matching bone marrow donors. After fi shing stem cells from each individual’s own blood, the researchers inserted a normal version of the ABCD1 gene into some of the cells and transplanted them back into the kids. The results were promising: ALD progression halted within 14 to 16 months. A year later neither child had further brain damage or leukemia (a side effect in some past gene therapy trials). The researchers have now treated a third individual and are preparing for larger trials in Europe and the U.S.

Source of Information : Scientific American Mind March-April 2010

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Multimedia Memory Boost

A video before bed or a recording played while asleep can enhance learning

Listen and Learn

Learning by listening to information as we sleep has long been a mainstay of science fiction—and wishful thinking— but a new study suggests the idea may not be so farfetched. What we hear during deep sleep can strengthen memories of information learned while awake. Researchers at Northwestern University taught 12 subjects to associate 50 images with specifi c positions on a computer screen. When the subjects saw each image, they also heard a matching noise—for instance, on seeing a cat, they heard a meow. Then the subjects each took a 60 to 80minute nap. While they were in slowwave sleep (a deepsleep phase marked by slow electrical oscillations in the brain), the researchers played the noises that matched 25 of the images they had been studying. On waking, the subjects were asked to perform the same image matching task. They were much better at correctly placing the images for which they had heard the noise cues while they napped. The participants reported they had no idea sounds had been played during their naps, and when asked to guess which sound cues they heard, they were just as likely to pick the wrong ones as the right ones. “We were certainly surprised,” says coauthor Ken Paller, director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Program at Northwestern, explaining that he did not expect such strong results. Although previous research has suggested that sleep alone can help consolidate memories, this study is the first to show that sound cues can strengthen specific spatial memories. Paller and his colleagues will next explore how long these effects last and whether aural cues can strengthen other types of memories as well. Until then, go ahead and play those French tapes while you snooze—it couldn’t hurt

A Movie and a Nap

Practice makes perfect, but can simply watching help, too? Yes, if you sleep on it right away, reports a study from the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience. Ysbrand Vander Werf and his colleagues tracked how well people learned to tap their fi ngers in a specifi c sequence—without any practice. Watching a video of the finger tapping task led to faster and more accurate fi rst attempts at the target sequence only when study participants slept within 12 hours of the video, before being tested. The finding not only points to a promising way to augment practicing when learning a new physical skill, it could also help people regain skills after injuries such as stroke.

Source of Information : Scientific American Mind March-April 2010

Listen and Learn

Learning by listening to information as we sleep has long been a mainstay of science fiction—and wishful thinking— but a new study suggests the idea may not be so farfetched. What we hear during deep sleep can strengthen memories of information learned while awake. Researchers at Northwestern University taught 12 subjects to associate 50 images with specifi c positions on a computer screen. When the subjects saw each image, they also heard a matching noise—for instance, on seeing a cat, they heard a meow. Then the subjects each took a 60 to 80minute nap. While they were in slowwave sleep (a deepsleep phase marked by slow electrical oscillations in the brain), the researchers played the noises that matched 25 of the images they had been studying. On waking, the subjects were asked to perform the same image matching task. They were much better at correctly placing the images for which they had heard the noise cues while they napped. The participants reported they had no idea sounds had been played during their naps, and when asked to guess which sound cues they heard, they were just as likely to pick the wrong ones as the right ones. “We were certainly surprised,” says coauthor Ken Paller, director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Program at Northwestern, explaining that he did not expect such strong results. Although previous research has suggested that sleep alone can help consolidate memories, this study is the first to show that sound cues can strengthen specific spatial memories. Paller and his colleagues will next explore how long these effects last and whether aural cues can strengthen other types of memories as well. Until then, go ahead and play those French tapes while you snooze—it couldn’t hurt

A Movie and a Nap

Practice makes perfect, but can simply watching help, too? Yes, if you sleep on it right away, reports a study from the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience. Ysbrand Vander Werf and his colleagues tracked how well people learned to tap their fi ngers in a specifi c sequence—without any practice. Watching a video of the finger tapping task led to faster and more accurate fi rst attempts at the target sequence only when study participants slept within 12 hours of the video, before being tested. The finding not only points to a promising way to augment practicing when learning a new physical skill, it could also help people regain skills after injuries such as stroke.

Source of Information : Scientific American Mind March-April 2010

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Sleep: too little and too much create fat

SLEEP'S effect on fat is becoming clearer. Having too much or too little piles on the worst kind of fat. Kristen Hairston and colleagues at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, monitored 1100 African and Hispanic Americans for five years. Both groups are at a high risk of obesity-related disorders. People under 40 gained 1.8 kilograms more on average if they got less than 5 hours of sleep per night than if they slept for 6 or 7 hours. Those regularly sleeping for more than 8 hours gained 0.8 kilograms more than the medium sleep group. CAT scans revealed increases in visceral fat, which accumulates around the internal organs and is particularly dangerous to health.

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

The writing is on the 60,OOO-year-old eggshells

COULD these lines etched into 60,000-year-old ostrich eggshells be the earliest signs of humans using graphic art to communicate? Until recently, the first consistent evidence of symbolic communication came from the geometric shapes that appear alongside rock art all over the world, which date to 40,000 years ago (New Scientist, 20 February, p 30). Older finds, like the 75,000-year-old engraved ochre chunks from the Blombos cave in South Africa, have mostly been one-offs and difficult to tell a part from meaningless doodles.

The engraved ostrich eggshells may change that. Since 1999, Pierre-jean Texier of the University of Bordeaux, France, and his colleagues have uncovered 270 fragments of shell at the DiepkloofRock Shelter in the Western Cape, South Africa.

They show the same symbols are used over and over again, and the team say there are signs that the symbols evolved over 5000 years. This long-term repetition is a hallmark of symbolic communication and a sign of modern human thinking, say the team (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, DOl: 1O.1073/pnas.0913047107). The eggshells were probably used as containers, and the markings may have indicated either the shells' contents or their owner. Texier points out that until recently, bushmen in the region carved geometric motifs on ostrich eggshells as a mark of ownership. If the symbols do signify ownership, it could have implications for the evolution of human cognition. lain Davidson, an Australian rock art specialist at the University of New England in Armidale, New South Wales, has suggested that marking ownership must have come after humans became self-aware. The eggshells could help to illuminate when this happened in this part of the world, he says.

Written language may have evolved more than once in human history. "judging from what we know about the evolution of art all over the world, there may have been many traditions that were born, lasted for some time and then vanished," says jean Clottes, former director of research at the Chauvet caves in southern France. "This may be one of them, most probably not the first and certainly not the last."

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

The engraved ostrich eggshells may change that. Since 1999, Pierre-jean Texier of the University of Bordeaux, France, and his colleagues have uncovered 270 fragments of shell at the DiepkloofRock Shelter in the Western Cape, South Africa.

They show the same symbols are used over and over again, and the team say there are signs that the symbols evolved over 5000 years. This long-term repetition is a hallmark of symbolic communication and a sign of modern human thinking, say the team (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, DOl: 1O.1073/pnas.0913047107). The eggshells were probably used as containers, and the markings may have indicated either the shells' contents or their owner. Texier points out that until recently, bushmen in the region carved geometric motifs on ostrich eggshells as a mark of ownership. If the symbols do signify ownership, it could have implications for the evolution of human cognition. lain Davidson, an Australian rock art specialist at the University of New England in Armidale, New South Wales, has suggested that marking ownership must have come after humans became self-aware. The eggshells could help to illuminate when this happened in this part of the world, he says.

Written language may have evolved more than once in human history. "judging from what we know about the evolution of art all over the world, there may have been many traditions that were born, lasted for some time and then vanished," says jean Clottes, former director of research at the Chauvet caves in southern France. "This may be one of them, most probably not the first and certainly not the last."

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Monday, July 26, 2010

Brain scans now catch chemicals too

A CHEMICAL produced during sex and l inked to addiction has been visualised in a scanner as it washes across rats' brains. The feat means that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a workhorse of neuroscience, can now be used to observe the flow of brain chemicals, not just oxygen - rich blood. By pin pointing increases in blood oxygenation in the brain in response to different events - a sign that specific groups of neurons are active - fMRI is responsible for some of the hottest findings about the brain . Now Alan jasan off at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and colleagues have extended its power.

His team repeatedly mutated a magnetic, iron-containing enzyme that "lights up" i n fMRI readings. With each mutation, the researchers tested its tendency to bind to dopamine, a learning and reward chemical in the brain involved in sex and addictive behaviors. Mutations that increased this tendency were combined, resulting in a molecule that was both magnetic and strongly attracted to dopamine.

The team injected the molecule into the brains of rats, in a region laden with dopamine-producing celis. When given a chemical that triggers dopamine release, that area "lit up" under fMRI (Nature Biotechnology, 001: 1O.103B/nbt.1609). Because the molecule must be injected into the brain, this kind of chemical- based fMRI won't be applied to humans anytime soon, says jasan off. b u t it could be used to probe addiction and disease using animals. His lab is now using the enzyme to view how dopamine-sensitive neurons across animal brains react when the chemical is produced in a specific region. The technique could also be used to probe dopamine's role in diseases such as Huntington's. The magnetic enzyme can in theory b e "evolved" t o b i n d t o other brain chemicals. Ewen Callaway

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

His team repeatedly mutated a magnetic, iron-containing enzyme that "lights up" i n fMRI readings. With each mutation, the researchers tested its tendency to bind to dopamine, a learning and reward chemical in the brain involved in sex and addictive behaviors. Mutations that increased this tendency were combined, resulting in a molecule that was both magnetic and strongly attracted to dopamine.

The team injected the molecule into the brains of rats, in a region laden with dopamine-producing celis. When given a chemical that triggers dopamine release, that area "lit up" under fMRI (Nature Biotechnology, 001: 1O.103B/nbt.1609). Because the molecule must be injected into the brain, this kind of chemical- based fMRI won't be applied to humans anytime soon, says jasan off. b u t it could be used to probe addiction and disease using animals. His lab is now using the enzyme to view how dopamine-sensitive neurons across animal brains react when the chemical is produced in a specific region. The technique could also be used to probe dopamine's role in diseases such as Huntington's. The magnetic enzyme can in theory b e "evolved" t o b i n d t o other brain chemicals. Ewen Callaway

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Sunday, July 25, 2010

Add oxygen to speed sobriety

BOOZE that has been treated so that you sober up faster afterwards may sound like a drinker's dream. But could end up being their down fall if it encourages heavy drinkers to consume even more alcohol. Kwang-il Kwon and his colleagues at Chungnam National University in Daejeon, South Korea, gave 30 men and 19 women 360 milliliters of a drink containing 19.5 per cent alcohol by volume, about the strength of fortified wine or sake. The drinks also contained 8, 20 or 25 parts per million of dissolved oxygen, which is known to play a role in alcohol breakdown by the body. It took about 5 hours for the blood alcohol levels of volunteers to reach zero. But Kwon's team found that on average, those whose drinks contained 20 or 25 ppm of oxygen went to zero 23 minutes and 27 minutes faster respectively than those who had the lowest-oxygen drinks (Alcoholism: Clinical &Experimental Research, DOl: 10.lll1/j.1530-0277.2010.01155.x).

The researchers suggest that enriching alcoholic drinks with oxygen might "allow individuals to become sober faster". 'The reduced time to a lower blood-alcohol concentration may reduce alcohol• related accidents," they write. A spokeswoman for the British Medical Association was unimpressed. "We would n't want a situation where people drank more simply because they would recover quicker."

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

The researchers suggest that enriching alcoholic drinks with oxygen might "allow individuals to become sober faster". 'The reduced time to a lower blood-alcohol concentration may reduce alcohol• related accidents," they write. A spokeswoman for the British Medical Association was unimpressed. "We would n't want a situation where people drank more simply because they would recover quicker."

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Saturday, July 24, 2010

Worm killer

IT WORKS for crops. Now a common organic pesticide could cure hundreds of millions of people of intestinal worms, if cash can be found for trials. More than 1 billion people, almost all of them living below the World Bank's poverty line, are infected with nematodes. While the worms don't usually kill, they stunt growth, cause anaemia and impair cognitive development. All this helps to "trap the 'bottom billion' in poverty", says Peter Hotez, a specialist in tropical diseases at George Washington University in Washington DC. The current treatment doesn't work well on all types of worms – and resistance is emerging. Now Raffi Aroian at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues have shown that the protein CrySB, produced by the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis and used as a crop pesticide, could act as an effective drug. An oral dose cleared around 70 per cent ofthe worms from infected mice (PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, DOl: 10.1371/journal.pntd.oooo614.t002). CrySB is about three times as effective as tribendimidin, the leading drug in development. A big obstacle is a dearth of funding for human trials, says Aroian.

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Friday, July 23, 2010

Time to accept that atheism, not god, is odd

IF YOU'RE one of those committed atheists in the Richard Dawkins mould who dreams of ridding the world of religious mumbo-jumbo, prepare yourself for a disappointment: there is no good evidence that education leads to secularisation. In fact, the more we learn about the "god instinct" and the refusal of religion to fade away under the onslaught of progress, the more the non-religious mindset looks like the odd man out. That is why anthropologists, psychologists and social scientists are now putting irreligion under the microscope in the same way they once did with religious belief. The aim is not to discredit atheism but to understand how so many people can override a way of thinking that seems to come so naturally. For that reason, atheists should welcome the new scrutiny. Atheism still has a great deal to commend it, not least that it doesn't need supernatural beings to make sense of the world. Let's hope the study of atheism leads to new insights into how to challenge such irrationality.

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Thursday, July 22, 2010

The power of persuasion

Coercive interrogation is ineffective and damaging, We need a more effective and humane approach

HOWLS of outrage greeted US Attorney General Eric Holder's decision to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed - who claims to have masterminded the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington - in a civilian court rather than before a military tribunal. The protesters' wish to see Mohammed treated as an enemy combatant is perhaps understandable, but in fact dealing with suspected terrorists in this way has a poor track record.

Since 2001, US military commissions have convicted just three detainees of perpetrating terrorist acts. Civilian courts have secured around 150 convictions. Why the difference?

The "enhanced interrogation" techniques sanctioned by the Bush administration after 9/n have surely not helped: as we report this week, they are both inhumane and ineffective. Practices such as sleep deprivation, isolation and forcing prisoners to maintain stress positions may fall outside the legal definition of torture but their impact can be just as damaging. And as with "proper" torture, they often fail to yield any information at all, or elicit worthless statements by causing detainees to lose touch with reality.

President Barack Obama has tried to draw a line under all this with the establishment ofa team of elite interrogators, the H ighValue Detainee Interrogation Group, that will only use "scientifically proven", humane techniques. But where these will come from is hard to know, as the research has simply not been done.

There is, however, a promising alternative to coercion, and though it may seem at first sight like a feeble strategy for dealing with people thought to be bent on mass murder, it has much to recommend it. It is simple persuasion, something that has been the subject of intense academic interest for decades, and that modern consumer societies have become very good at.

Here is a field in which science really can point to effective techniques for extracting useful information. We know, for example, that successful persuasion rests on the reputation of the person doing the persuading. This may help explain the civilian justice system's greater success at bringing terrorists to book: they have a much better reputation for fair dealing than the military tribunals system.

Commenting on the announcement that the alleged Christmas day bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab - who is to be tried by the civilian courts – is cooperating with the FBI, Holder said: "You are much more likely to get people to cooperate with us if their belief is that we are acting in a way that is consistent with American values."

If the security services want to improve their reputation there is a proven way: reputation requires trust, and trust rests on openness. For that reason, the workings of Obama's new interrogation group must be more transparent than the shadowy world of

Guantanamo Bay. That would begin to repair the damage done to America's reputation. It might also deliver the result that is surely to be desired: better intelligence, more terrorists behind bars, and less torture .

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

HOWLS of outrage greeted US Attorney General Eric Holder's decision to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed - who claims to have masterminded the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington - in a civilian court rather than before a military tribunal. The protesters' wish to see Mohammed treated as an enemy combatant is perhaps understandable, but in fact dealing with suspected terrorists in this way has a poor track record.

Since 2001, US military commissions have convicted just three detainees of perpetrating terrorist acts. Civilian courts have secured around 150 convictions. Why the difference?

The "enhanced interrogation" techniques sanctioned by the Bush administration after 9/n have surely not helped: as we report this week, they are both inhumane and ineffective. Practices such as sleep deprivation, isolation and forcing prisoners to maintain stress positions may fall outside the legal definition of torture but their impact can be just as damaging. And as with "proper" torture, they often fail to yield any information at all, or elicit worthless statements by causing detainees to lose touch with reality.

President Barack Obama has tried to draw a line under all this with the establishment ofa team of elite interrogators, the H ighValue Detainee Interrogation Group, that will only use "scientifically proven", humane techniques. But where these will come from is hard to know, as the research has simply not been done.

There is, however, a promising alternative to coercion, and though it may seem at first sight like a feeble strategy for dealing with people thought to be bent on mass murder, it has much to recommend it. It is simple persuasion, something that has been the subject of intense academic interest for decades, and that modern consumer societies have become very good at.

Here is a field in which science really can point to effective techniques for extracting useful information. We know, for example, that successful persuasion rests on the reputation of the person doing the persuading. This may help explain the civilian justice system's greater success at bringing terrorists to book: they have a much better reputation for fair dealing than the military tribunals system.

Commenting on the announcement that the alleged Christmas day bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab - who is to be tried by the civilian courts – is cooperating with the FBI, Holder said: "You are much more likely to get people to cooperate with us if their belief is that we are acting in a way that is consistent with American values."

If the security services want to improve their reputation there is a proven way: reputation requires trust, and trust rests on openness. For that reason, the workings of Obama's new interrogation group must be more transparent than the shadowy world of

Guantanamo Bay. That would begin to repair the damage done to America's reputation. It might also deliver the result that is surely to be desired: better intelligence, more terrorists behind bars, and less torture .

Source of Information : New Scientist March 6 2010

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

The Riddle of Flavor

Seeing that your tongue detects only a few different flavor types, it seems odd that we can distinguish between a roast beef and a rutabaga (never mind between different vintages of Zinfandel).

A good part of this disparity is thanks to your nose’s chemical-sensing abilities. As you eat, volatile chemicals stream off the food in your mouth, rise through the back of your throat, enter your nasal cavity, and arrive at the same odor detectors you saw on page 124. These detectors work in conjunction with the primary tasting ability of your tongue to generate endless variations of flavor. In fact, some studies suggest that the tongue is a bit player in the sensation of taste, and that 80 percent of taste takes place in your nasal cavity.

For many years, food scientists thought the interplay between tongue and nose was the whole story behind taste. However, more recent research shows that taste involves an impossibly complex mix of factors:

• Texture. The feel of food as it gives way to your teeth and mixes in your mouth changes how you feel about it. For example, study participants rank a thick cheese sauce as tasting cheesier, even if extra flour is the only difference. And if you doubt the power of texture, try putting some hot, crispy french fries in a plastic bag for a few minutes, then see if you feel the same way about the identically flavored soggy sticks that emerge. Or compare the sweetness of a fizzy drink with an identical one that went flat half an hour ago.

• Temperature. Hot food is tastier because its volatile chemicals are more likely to drift to your nasal cavity and trigger different odor receptors. However, even without this factor, the temperature of food influences your overall experience. Think, for example, how soup warms your stomach, and why you’ll never mistake a spoonful of ice cream for butter or yogurt.

• Touch (or pain). Some sensations that happen on the tongue have nothing to do with your taste buds. Examples include the tingle of alcohol, the coolness of mint, and the sear of hot spices. These compounds mess with the other nerve endings in your tongue, and some, like hot chile peppers, actually cause pain. (Chile-pepper survival advice: Because the active ingredient is an oil, water does little to wash it away. The fat in whole milk or the alcolhol in beer dissolve it more easily. By comparison, the singe of mustard and wasabi is shorter-lived because most of its kick comes from the odor receptors in the nasal cavity.)

• Appearance. Cooks are taught that the first bite is with the eye, and there’s a solid body of science that suggests they’re right. Just changing the color of foods causes people to imagine different tastes. For example, study participants will stubbornly describe orange-flavored, yellow-colored Jell-O as tasting like pineapples. A similar effect has been noticed with white wine that’s dyed red.

• Combinations. When you pair different flavors, the result is more than the sum of its parts. For example, tasters may claim a strawberry tastes more strongly like strawberries when it’s diluted with water and sweetened with sugar.

• Expectations. There’s a reason that food tastes better when you dine at a fine restaurant. The framework of assumptions and expectations you have when you approach a meal conditions your brain to perceive it in a certain way. Current emotions and past experiences are particularly powerful: from fond childhood memories of Grandma’s apple pie to the time you projectile vomited mint-chocolate ice cream on the Tilt-A-Whirl.

In short, your perception of flavor relies on all your senses, your memories, and your current state of mind. It’s one of your body’s great surprises: A simple sense that seems to involve little more than a few bumps on your tongue just might be your body’s strangest door of perception.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

A good part of this disparity is thanks to your nose’s chemical-sensing abilities. As you eat, volatile chemicals stream off the food in your mouth, rise through the back of your throat, enter your nasal cavity, and arrive at the same odor detectors you saw on page 124. These detectors work in conjunction with the primary tasting ability of your tongue to generate endless variations of flavor. In fact, some studies suggest that the tongue is a bit player in the sensation of taste, and that 80 percent of taste takes place in your nasal cavity.

For many years, food scientists thought the interplay between tongue and nose was the whole story behind taste. However, more recent research shows that taste involves an impossibly complex mix of factors:

• Texture. The feel of food as it gives way to your teeth and mixes in your mouth changes how you feel about it. For example, study participants rank a thick cheese sauce as tasting cheesier, even if extra flour is the only difference. And if you doubt the power of texture, try putting some hot, crispy french fries in a plastic bag for a few minutes, then see if you feel the same way about the identically flavored soggy sticks that emerge. Or compare the sweetness of a fizzy drink with an identical one that went flat half an hour ago.

• Temperature. Hot food is tastier because its volatile chemicals are more likely to drift to your nasal cavity and trigger different odor receptors. However, even without this factor, the temperature of food influences your overall experience. Think, for example, how soup warms your stomach, and why you’ll never mistake a spoonful of ice cream for butter or yogurt.

• Touch (or pain). Some sensations that happen on the tongue have nothing to do with your taste buds. Examples include the tingle of alcohol, the coolness of mint, and the sear of hot spices. These compounds mess with the other nerve endings in your tongue, and some, like hot chile peppers, actually cause pain. (Chile-pepper survival advice: Because the active ingredient is an oil, water does little to wash it away. The fat in whole milk or the alcolhol in beer dissolve it more easily. By comparison, the singe of mustard and wasabi is shorter-lived because most of its kick comes from the odor receptors in the nasal cavity.)

• Appearance. Cooks are taught that the first bite is with the eye, and there’s a solid body of science that suggests they’re right. Just changing the color of foods causes people to imagine different tastes. For example, study participants will stubbornly describe orange-flavored, yellow-colored Jell-O as tasting like pineapples. A similar effect has been noticed with white wine that’s dyed red.

• Combinations. When you pair different flavors, the result is more than the sum of its parts. For example, tasters may claim a strawberry tastes more strongly like strawberries when it’s diluted with water and sweetened with sugar.

• Expectations. There’s a reason that food tastes better when you dine at a fine restaurant. The framework of assumptions and expectations you have when you approach a meal conditions your brain to perceive it in a certain way. Current emotions and past experiences are particularly powerful: from fond childhood memories of Grandma’s apple pie to the time you projectile vomited mint-chocolate ice cream on the Tilt-A-Whirl.

In short, your perception of flavor relies on all your senses, your memories, and your current state of mind. It’s one of your body’s great surprises: A simple sense that seems to involve little more than a few bumps on your tongue just might be your body’s strangest door of perception.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Supertasters

You eat a varied diet and plenty of vegetables. Your best friend subsists on diet soda and cheese pizza. Is she hopelessly spoiled, or is her perception of taste just wired differently? Modern science might have the answer.

In recent years, scientists have begun discussing supertasters—individuals who experience taste more strongly than others, and who are more likely to be picky eaters. Supertasters are particularly sensitive to bitter flavors (which they often shun). Research suggests that in the U.S., roughly 35 percent of women and 15 percent of men are supertasters.

If all this sounds made up, you’ll be surprised to hear that a scientific test can sift out supertasters. The test is remarkably simple. Participants taste a solution that includes a chemical like propylthiouracil. Many people find this taste mildly unpleasant, but supertasters find it stomach-churningly awful. Still other people (called, rather sadly, nontasters) say the mystery chemical has no taste at all.

You can test your own tasting abilities using an at-home kit, like the kind sold on http://supertastertest.com. Or you can try the crude experiment discussed next, which uses dye to help you estimate the number of taste buds on your tongue. (The current thinking is that supertasters have a heavier concentration of taste buds on their tongues, but this is probably not the only reason for supertasting.)

Here’s how to perform the test:

1. Gather up your supplies: some blue food coloring, a piece of paper with a 7-millimeter (about a quarter-inch) hole punched through it, and a magnifying glass.

2. Using a cotton swab, rub some of the food coloring onto the tip of your tongue. Your tongue will absorb the dye, but the tiny papillae will stay pink. This is where your taste buds are.

3. Put the piece of paper over the front part of your tongue.

4. Using the magnifying glass, look at the hole. Now count how many pink dots you see within the hole. A score of fewer than 15 suggests you’re a nontaster. A count of from 15 to 35 ranks you as normal, while anything greater suggests supertasting abilities.

Supertasters don’t necessarily have a better sense of taste than normal people. It all depends on your perspective. Yes, supertasters have a stronger reaction to certain tastes, but there’s still much to be said for a cultured palate—in other words, a broad love of food honed through years of comparative tasting.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

In recent years, scientists have begun discussing supertasters—individuals who experience taste more strongly than others, and who are more likely to be picky eaters. Supertasters are particularly sensitive to bitter flavors (which they often shun). Research suggests that in the U.S., roughly 35 percent of women and 15 percent of men are supertasters.

If all this sounds made up, you’ll be surprised to hear that a scientific test can sift out supertasters. The test is remarkably simple. Participants taste a solution that includes a chemical like propylthiouracil. Many people find this taste mildly unpleasant, but supertasters find it stomach-churningly awful. Still other people (called, rather sadly, nontasters) say the mystery chemical has no taste at all.

You can test your own tasting abilities using an at-home kit, like the kind sold on http://supertastertest.com. Or you can try the crude experiment discussed next, which uses dye to help you estimate the number of taste buds on your tongue. (The current thinking is that supertasters have a heavier concentration of taste buds on their tongues, but this is probably not the only reason for supertasting.)

Here’s how to perform the test:

1. Gather up your supplies: some blue food coloring, a piece of paper with a 7-millimeter (about a quarter-inch) hole punched through it, and a magnifying glass.

2. Using a cotton swab, rub some of the food coloring onto the tip of your tongue. Your tongue will absorb the dye, but the tiny papillae will stay pink. This is where your taste buds are.

3. Put the piece of paper over the front part of your tongue.

4. Using the magnifying glass, look at the hole. Now count how many pink dots you see within the hole. A score of fewer than 15 suggests you’re a nontaster. A count of from 15 to 35 ranks you as normal, while anything greater suggests supertasting abilities.

Supertasters don’t necessarily have a better sense of taste than normal people. It all depends on your perspective. Yes, supertasters have a stronger reaction to certain tastes, but there’s still much to be said for a cultured palate—in other words, a broad love of food honed through years of comparative tasting.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Monday, July 19, 2010

Why Do You Crave Sugar, Salt, and Fat?

Your tongue has a limited variety of taste receptors because sugar, salt, and fat were the flavors most important for human survival over the last few million years of evolution. Your tongue craves sweetness because it signals ripe fruit. You yearn for salt because it’s an essential compound for basic body function. You long for fat because it’s an extremely dense source of dietary energy. On the other side of things, sourness can alert you to spoiled food, and bitterness can warn you about poisonous substances.

Our sense of taste is a great tool when we need to select nutritious, non-toxic foods from a natural environment. However, its effects aren’t as positive when we use it to guide food creation—for example, when we engineer heavily refined foods like candy-coated breakfast cereal. In this situation, our natural preference for sweet and salty runs rampant, producing foods that are literally too much of a good thing. These foods still taste

good on our tongues, but over time they can throw our bodies seriously off kilter.

The good news is that learned associations can gradually trump our built-in drive for sugar, salt, and fat. After all, many highly prized tastes involve a complex assortment of flavors along with the sour or bitter notes we normally avoid. For example, chocolate, coffee, beer, citrus peel, and greens like escarole all have strong bitter notes that we enjoy when matched with other flavors. There’s a good evolutionary reason for this flexibility— generations ago, humans who could discover new, untapped sources of food had a huge survival advantage.

This is particularly significant if you’re a parent and you want to expand your kid’s taste universe beyond chicken nuggets and plain pasta. The best advice is to present new foods, several times, with no conditions. Avoid resorting to bribery, bargaining, or threats, all of which place a taste “value” on food. (For example, using chocolate as a reward for eating spinach teaches that chocolate is desirable and spinach is not.) While you’re unlikely to find a child who prefers rapini to peanut butter, in time we can all learn to love a wide range of flavors.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Our sense of taste is a great tool when we need to select nutritious, non-toxic foods from a natural environment. However, its effects aren’t as positive when we use it to guide food creation—for example, when we engineer heavily refined foods like candy-coated breakfast cereal. In this situation, our natural preference for sweet and salty runs rampant, producing foods that are literally too much of a good thing. These foods still taste

good on our tongues, but over time they can throw our bodies seriously off kilter.

The good news is that learned associations can gradually trump our built-in drive for sugar, salt, and fat. After all, many highly prized tastes involve a complex assortment of flavors along with the sour or bitter notes we normally avoid. For example, chocolate, coffee, beer, citrus peel, and greens like escarole all have strong bitter notes that we enjoy when matched with other flavors. There’s a good evolutionary reason for this flexibility— generations ago, humans who could discover new, untapped sources of food had a huge survival advantage.

This is particularly significant if you’re a parent and you want to expand your kid’s taste universe beyond chicken nuggets and plain pasta. The best advice is to present new foods, several times, with no conditions. Avoid resorting to bribery, bargaining, or threats, all of which place a taste “value” on food. (For example, using chocolate as a reward for eating spinach teaches that chocolate is desirable and spinach is not.) While you’re unlikely to find a child who prefers rapini to peanut butter, in time we can all learn to love a wide range of flavors.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Sunday, July 18, 2010

Odor Fatigue

Your brain quickly adapts to new smells. What smells pungently strong on the first sniff becomes almost undetectable a few minutes later. This phenomenon, called odor fatigue, is similar to the way the hum of an air conditioner fades into background noise, but odor fatigue is more powerful. That’s because once you lose track of a smell, you can’t will yourself to get it back—at least not without first leaving the room and smelling something else.

Odor fatigue makes perfect sense when you consider the evolutionary role of smell. Your body is more interested in using smell to detect things than it is in keeping track of them. Once you notice a smell and decide how you want to react, it’s time to move on so you can detect the next potentially important odor.

Now that you understand how odor fatigue lets you ignore prolonged smells, there are a few practical bits of advice to consider:

• To determine if an object or room in your house smells, start by walking out the door and giving your nose a break. Then step back inside and pay attention.

• To determine if you have body-odor issues, you’ll need the help of a friend who can sniff you out.

• Just because you can ignore a smell doesn’t mean you should. Irritants and even toxins, ranging from cleaning products to cigarette smoke, are easy to ignore if you live with them, but they might not be so easy on your lungs. If in doubt, open a window and get some fresh air.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Odor fatigue makes perfect sense when you consider the evolutionary role of smell. Your body is more interested in using smell to detect things than it is in keeping track of them. Once you notice a smell and decide how you want to react, it’s time to move on so you can detect the next potentially important odor.

Now that you understand how odor fatigue lets you ignore prolonged smells, there are a few practical bits of advice to consider:

• To determine if an object or room in your house smells, start by walking out the door and giving your nose a break. Then step back inside and pay attention.

• To determine if you have body-odor issues, you’ll need the help of a friend who can sniff you out.

• Just because you can ignore a smell doesn’t mean you should. Irritants and even toxins, ranging from cleaning products to cigarette smoke, are easy to ignore if you live with them, but they might not be so easy on your lungs. If in doubt, open a window and get some fresh air.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Saturday, July 17, 2010

Exploring Your Frequency Response Curve

An average young person can hear a staggering range of sound vibrations from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. (A Hertz is one vibration per second. So 20,000 Hz is a vibration that happens 20,000 times each second.) Of course, you won’t hear all pitches equally well. The middle-range pitches are the easiest to detect. A sound that’s similarly loud but extremely high-pitched will seem much quieter to your ear. You’ll notice a similar fall-off as you descend to the rumbles of low-frequency sound, although you’ll begin to feel them reverberate through your body.

As you age, the upper range of your hearing shrinks. For example, the hearing of a normal, middle-aged adult tops out at a significantly lower (but still impressive) 14,000 Hz. This change has been used to some effect by clever people on both sides of the age divide. For example, one company sells a sound device called the Mosquito Ultrasonic Teen Repellent (www.noloitering.ca). It emits an annoying sound that only young people can hear. Put it in a place where you don’t want crowds of teenagers to loiter—say, a mall parking lot—and it’s sure to drive them away. A similarly inventive product is the Teen Buzz ringtone (www.teenbuzz.org). Teenagers use it to announce text messages on their cell phones without alerting teachers and other authority figures in the over-30 crowd.

To test your own hearing and find the highest frequency you can detect, try an online hearing test (like the one on www.phys.unsw.edu.au/jw/hearing.html). Of course, these tests depend on some factors you can’t control, such as the quality of your speakers and the noise your computer makes, so they’re not perfectly accurate.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

As you age, the upper range of your hearing shrinks. For example, the hearing of a normal, middle-aged adult tops out at a significantly lower (but still impressive) 14,000 Hz. This change has been used to some effect by clever people on both sides of the age divide. For example, one company sells a sound device called the Mosquito Ultrasonic Teen Repellent (www.noloitering.ca). It emits an annoying sound that only young people can hear. Put it in a place where you don’t want crowds of teenagers to loiter—say, a mall parking lot—and it’s sure to drive them away. A similarly inventive product is the Teen Buzz ringtone (www.teenbuzz.org). Teenagers use it to announce text messages on their cell phones without alerting teachers and other authority figures in the over-30 crowd.

To test your own hearing and find the highest frequency you can detect, try an online hearing test (like the one on www.phys.unsw.edu.au/jw/hearing.html). Of course, these tests depend on some factors you can’t control, such as the quality of your speakers and the noise your computer makes, so they’re not perfectly accurate.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Friday, July 16, 2010

We’re All Color Blind

Black-and-white vision is a one-dimensional affair. A given shade can get blacker or whiter, but that’s it. Color vision (by which we mean human color vision) has three variables. You can modify any color by changing the amount of red, green, or blue in it. This mix of colors triggers different cones in your eye, creating the perceptual experience of seeing a single, specific shade.

But some animals aren’t limited to three types of cones. Consider birds, whose eyes have a number of advantages over yours. Their eyes are stacked with more cone, and these cones are arranged in larger patches (or in multiple patches) and packed more closely together. This arrangement gives some birds spectacularly sharp vision over long distances. But the most remarkable feature of birds’ eyes is how their cones work. Unlike your eyes, which have three types of cones, birds’ eyes have four or five distinct types of cones.

So what does this mean? Imagine meeting a pigeon and traveling with it to the countryside. Your eyes will collect the same reflected light as the pigeon’s eyes. You’ll see the same scenery. But the pigeon will perceive that light differently. Its eyes will break the rolling hills into a mix of four primary colors, while you translate them to a measly combination of three. For the pigeon, the contrast of certain wavelengths of light will become more dramatic, allowing it to spot details that your eyes miss. The difference is a little like leaping from black-and-white to color vision. Ultimately—and there’s no way around this—the pigeon will get a subtler, more nuanced view of the outside world.

So the next time an interior decorator scolds you for mistaking pistachio green for chartreuse, remind yourself that in the eyes of a pigeon, we’re all color-blind.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

But some animals aren’t limited to three types of cones. Consider birds, whose eyes have a number of advantages over yours. Their eyes are stacked with more cone, and these cones are arranged in larger patches (or in multiple patches) and packed more closely together. This arrangement gives some birds spectacularly sharp vision over long distances. But the most remarkable feature of birds’ eyes is how their cones work. Unlike your eyes, which have three types of cones, birds’ eyes have four or five distinct types of cones.

So what does this mean? Imagine meeting a pigeon and traveling with it to the countryside. Your eyes will collect the same reflected light as the pigeon’s eyes. You’ll see the same scenery. But the pigeon will perceive that light differently. Its eyes will break the rolling hills into a mix of four primary colors, while you translate them to a measly combination of three. For the pigeon, the contrast of certain wavelengths of light will become more dramatic, allowing it to spot details that your eyes miss. The difference is a little like leaping from black-and-white to color vision. Ultimately—and there’s no way around this—the pigeon will get a subtler, more nuanced view of the outside world.

So the next time an interior decorator scolds you for mistaking pistachio green for chartreuse, remind yourself that in the eyes of a pigeon, we’re all color-blind.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Thursday, July 15, 2010

Seeing in Color (and at Night)

Your retina is packed with light-sensing cells. But you may not realize that these light detectors come in two flavors:

• Rods. These are the most numerous light-sensing cells in your eyes. They’re extremely efficient at collecting light and continue working even in near-darkness. For this reason, your rods power your night vision. However, rods don’t distinguish between different colors.

• Cones. These cells are less sensitive than rods (meaning they need more light to do their work), but they’re able to perceive fine detail and color. Your eyes have three types of cones, which give you the ability to perceive three primary colors (red, green, and blue), provided there’s enough light for your cones to function.

Rods are spread throughout the sides of your eye. Cones are packed into a small region in the middle of your eye.

This combination of rods and cones gives your eye the best of both worlds—highly sensitive black-and-white vision you can use to creep around at night, and sharp color vision that catches more detail during the day. Although your brain switches effortlessly between the two, it takes 30 minutes of darkness to develop your best night vision. That’s because night vision requires chemical changes in your eye that make your rods more sensitive.

A short blast of ordinary light usually resets your vision from dark- to lightadjusted. However, dim red light doesn’t trigger this change because your dark-adjusted rods are naturally tuned to the blue end of the light spectrum, and they have a hard time picking up the color red. That’s why astronomical observatories and submarines use red light to illuminate dials and switches—it provides enough light for operators to see their instruments in a darkened environment, but it doesn’t disrupt their night vision.

Incidentally, most color-blind people have the same three types of cones as everyone else, but their cones don’t function normally. These people may have trouble discriminating between certain shades of color, but the effect is usually minor. Often, it goes unnoticed until they try a color-vision test (like the spot-the-number test at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishihara_color_test). However, people with rarer, more serious forms of color-blindness may have only two functioning types of cones. They may be unable to distinguish purple from blue or red from yellow, except by the slight changes in brightness of the hues, not by the colors themselves.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

• Rods. These are the most numerous light-sensing cells in your eyes. They’re extremely efficient at collecting light and continue working even in near-darkness. For this reason, your rods power your night vision. However, rods don’t distinguish between different colors.

• Cones. These cells are less sensitive than rods (meaning they need more light to do their work), but they’re able to perceive fine detail and color. Your eyes have three types of cones, which give you the ability to perceive three primary colors (red, green, and blue), provided there’s enough light for your cones to function.

Rods are spread throughout the sides of your eye. Cones are packed into a small region in the middle of your eye.

This combination of rods and cones gives your eye the best of both worlds—highly sensitive black-and-white vision you can use to creep around at night, and sharp color vision that catches more detail during the day. Although your brain switches effortlessly between the two, it takes 30 minutes of darkness to develop your best night vision. That’s because night vision requires chemical changes in your eye that make your rods more sensitive.

A short blast of ordinary light usually resets your vision from dark- to lightadjusted. However, dim red light doesn’t trigger this change because your dark-adjusted rods are naturally tuned to the blue end of the light spectrum, and they have a hard time picking up the color red. That’s why astronomical observatories and submarines use red light to illuminate dials and switches—it provides enough light for operators to see their instruments in a darkened environment, but it doesn’t disrupt their night vision.

Incidentally, most color-blind people have the same three types of cones as everyone else, but their cones don’t function normally. These people may have trouble discriminating between certain shades of color, but the effect is usually minor. Often, it goes unnoticed until they try a color-vision test (like the spot-the-number test at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishihara_color_test). However, people with rarer, more serious forms of color-blindness may have only two functioning types of cones. They may be unable to distinguish purple from blue or red from yellow, except by the slight changes in brightness of the hues, not by the colors themselves.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

Flawed Vision

Our eyes have a clear and obvious design flaw—they often fail to focus properly. This is a far greater problem than the eye’s other quirks, such as its blind spot and its inability to see certain colors. So why should such an elegant, intricate organ have such a glaring hitch?

Although there’s no definitive answer, many experts now believe that the problem has something to do with modern life. In the distant past, our ancestors spent most of their time wandering the savanna and staring into the distance. In today’s world, we spend far more time on near work—close-up activities like reading, writing, and drawing. During childhood, these activities may gradually reorient the eye from its natural state of mild farsightedness to the far more common condition of adult nearsightedness. In fact, our vision may have worked far better in the era before the invention of corrective eyewear (which was developed relatively recently, in 13th-century Italy).

Although this is all somewhat speculative, it may eventually lead to a way to prevent eye trouble. For example, children might be able to perform far-vision exercises to counterbalance the overload of near work. But for now, there’s no solution other than glasses and contact lenses, and there’s no evidence to suggest that you can help your eyes by cutting down on modern activities in adulthood. So now that your vision is already screwy, it’s safe to keep reading, writing, watching television, and surfing the Web.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Although there’s no definitive answer, many experts now believe that the problem has something to do with modern life. In the distant past, our ancestors spent most of their time wandering the savanna and staring into the distance. In today’s world, we spend far more time on near work—close-up activities like reading, writing, and drawing. During childhood, these activities may gradually reorient the eye from its natural state of mild farsightedness to the far more common condition of adult nearsightedness. In fact, our vision may have worked far better in the era before the invention of corrective eyewear (which was developed relatively recently, in 13th-century Italy).

Although this is all somewhat speculative, it may eventually lead to a way to prevent eye trouble. For example, children might be able to perform far-vision exercises to counterbalance the overload of near work. But for now, there’s no solution other than glasses and contact lenses, and there’s no evidence to suggest that you can help your eyes by cutting down on modern activities in adulthood. So now that your vision is already screwy, it’s safe to keep reading, writing, watching television, and surfing the Web.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Removing Earwax

On a good day, earwax does its job, trapping foreign material and gradually moving up your ear canal to the opening of your ear. There, it dries up and eventually falls out, its job done.

But earwax isn’t always so accommodating. Many people have particularly hard or sticky earwax. It becomes trapped inside the ear canal and can eventually plug it up, causing pain and blocking sound. In fact, this problem can happen to anyone, because the consistency of earwax can change abruptly and without explanation.

So what should you do about earwax? Don’t start digging with a cotton swab. Contrary to what you might have heard, they are safe for removing earwax, but only if you limit your swabbing to the opening of your ear canal and resist the urge to plunge in. Deeper swabbing is likely to compact wax, turning a partial blockage into a complete one. It’s also dangerous, because it risks damaging the sensitive eardrum or scratching the earcanal skin, which can lead to a painful infection.

So what can you do? If you don’t have problem earwax, you don’t need to do anything— after all, the wax in your ear canal belongs there, and it will migrate out in its own good time. But if you’re prone to wax of the ear-clogging variety, a simple practice can help prevent blockages. Put two or three drops of mineral oil into each ear every day (using an eye dropper). Over a couple of weeks, this softens wax so that you can remove it with a gentle flush of water. If your ear is completely blocked, head to your family doctor, who can wash it out or scoop it out using special tools.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

But earwax isn’t always so accommodating. Many people have particularly hard or sticky earwax. It becomes trapped inside the ear canal and can eventually plug it up, causing pain and blocking sound. In fact, this problem can happen to anyone, because the consistency of earwax can change abruptly and without explanation.

So what should you do about earwax? Don’t start digging with a cotton swab. Contrary to what you might have heard, they are safe for removing earwax, but only if you limit your swabbing to the opening of your ear canal and resist the urge to plunge in. Deeper swabbing is likely to compact wax, turning a partial blockage into a complete one. It’s also dangerous, because it risks damaging the sensitive eardrum or scratching the earcanal skin, which can lead to a painful infection.

So what can you do? If you don’t have problem earwax, you don’t need to do anything— after all, the wax in your ear canal belongs there, and it will migrate out in its own good time. But if you’re prone to wax of the ear-clogging variety, a simple practice can help prevent blockages. Put two or three drops of mineral oil into each ear every day (using an eye dropper). Over a couple of weeks, this softens wax so that you can remove it with a gentle flush of water. If your ear is completely blocked, head to your family doctor, who can wash it out or scoop it out using special tools.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Monday, July 12, 2010

Back Strengthening

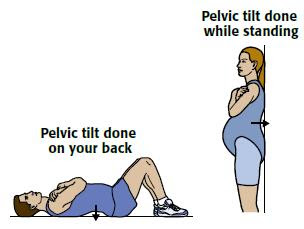

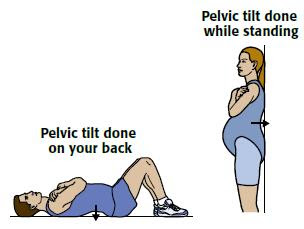

Weak back muscles just can’t support your spine and battle gravity for an entire day. If you want your spine to stay healthy and pain-free, your best bet is to strengthen your back muscles with regular exercise.

Ideally, you’ll fortify your back with aerobic exercise (walking, running, dancing, and so on) and regular strength-training. Core exercises like abdominal crunches are particularly helpful because they reinforce the back and abdominal muscles that stabilize and support your spine.

The single most useful exercise for strengthening your back and relieving back pain is surprisingly simple and remarkably portable. You can do it on the floor of your home gym, in the chair at your office desk, or against the wall at a cocktail party. Pregnant women can use it to alleviate the excruciating backaches caused by their still-in-progress bundle of joy (on the floor up to the fourth month, against a wall thereafter). It goes by many names, including the one used in this chapter: the pelvic tilt.

If you have a pre-existing back condition or chronic back pain, doing the wrong kind of exercise (or doing the right exercise in the wrong way) could aggravate the problem. If you’re in doubt, check with your doctor, and never perform a back exercise that causes any sort of pain.

Here’s how to do the pelvic tilt:

1. Lie on your back with your knees bent and your hands resting at your sides. (Or stand so you put your whole body—heels, bottom, and shoulders—against a wall.)

2. Tighten your abdominal muscles and squeeze your lower back down against the floor (or wall, or chair). Alternatively, you can rest your hand on the small of your back and push against that.

3. Hold the squeeze for five seconds, but don’t hold your breath.

4. Relax your muscles, then repeat this sequence 10 to 15 times.

You can find many of the core exercises cited in this chapter described online. To get started, you’ll find good collections of back exercises at www.mayoclinic.com/health/back-pain/LB00001_D and http://tinyurl.com/cyybg9. (To save yourself some typing, you can find this link on the Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com.) Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Ideally, you’ll fortify your back with aerobic exercise (walking, running, dancing, and so on) and regular strength-training. Core exercises like abdominal crunches are particularly helpful because they reinforce the back and abdominal muscles that stabilize and support your spine.

The single most useful exercise for strengthening your back and relieving back pain is surprisingly simple and remarkably portable. You can do it on the floor of your home gym, in the chair at your office desk, or against the wall at a cocktail party. Pregnant women can use it to alleviate the excruciating backaches caused by their still-in-progress bundle of joy (on the floor up to the fourth month, against a wall thereafter). It goes by many names, including the one used in this chapter: the pelvic tilt.

If you have a pre-existing back condition or chronic back pain, doing the wrong kind of exercise (or doing the right exercise in the wrong way) could aggravate the problem. If you’re in doubt, check with your doctor, and never perform a back exercise that causes any sort of pain.

Here’s how to do the pelvic tilt:

1. Lie on your back with your knees bent and your hands resting at your sides. (Or stand so you put your whole body—heels, bottom, and shoulders—against a wall.)

2. Tighten your abdominal muscles and squeeze your lower back down against the floor (or wall, or chair). Alternatively, you can rest your hand on the small of your back and push against that.

3. Hold the squeeze for five seconds, but don’t hold your breath.

4. Relax your muscles, then repeat this sequence 10 to 15 times.

You can find many of the core exercises cited in this chapter described online. To get started, you’ll find good collections of back exercises at www.mayoclinic.com/health/back-pain/LB00001_D and http://tinyurl.com/cyybg9. (To save yourself some typing, you can find this link on the Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com.)

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Sleeping posture

We’re not about to crawl between the sheets with you and prescribe stiff rules about how to position your sleeping body. However, if you already suffer from bouts of back pain (whether caused by long hours of office work, heavy lifting, or pregnancy), you might find that sleeping in your regular positions is about as comfortable as having a prickly pear in your pajama bottoms. In this situation, you can try two tricks. First, if you’re a back sleeper, place a pillow under your knees. This takes the strain off your lower back. (If you want to adopt this position permanently, look for a wedgeshaped specialty pillow at a pharmacy or health store.) Second, if you sleep on your side, put a pillow between your knees. Again, this helps keep your spine in the straight, neutral alignment it likes best.

If you’re still not getting any relief for a sore back, consider the pelvic-tilt exercise. Not only can it relieve back pain, but it doesn’t require you to climb out of bed.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

If you’re still not getting any relief for a sore back, consider the pelvic-tilt exercise. Not only can it relieve back pain, but it doesn’t require you to climb out of bed.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Saturday, July 10, 2010

Lifting posture

One of the easiest ways to injure your back is through careless lifting. A proper lifting technique looks a bit like the squat exercise. Like the squat, it involves crouching down and using the strong muscles in your legs to do the brunt of the lifting, minimizing the stress you put on your back and reducing the amount you bend your spine. A little preparation can make all the difference in proper lifting. Before you grab the object in front of you, adopt a wide, crouched stance. Make sure your feet rest firmly on the floor and that your back is straight, not hunched. Stand slowly, avoid twisting to the side, and concentrate on pushing with your legs, rather than pulling with your back.

If you struggle with back pain, experts will tell you to use proper lifting for any object below waist height—even a dropped pencil.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

If you struggle with back pain, experts will tell you to use proper lifting for any object below waist height—even a dropped pencil.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Friday, July 9, 2010

Sitting posture

It’s often said that the rear end is the most heavily used part of the human body. If you’re an average person living in the modern world, you spend a lot of time pressing your behind into soft, yielding pieces of furniture. In fact, you probably spend more time sitting down (whether it’s working, eating, driving, watching television, or reading fine books like this one) than you spend in virtually any other position.

With all our experience sitting, it’s a bit disappointing to learn that most of us aren’t very good at it. Proper sitting is surprisingly hard work, especially when you add computers, telephones, and office work into the mix. Part of the problem is that sitting “at the ready” quickly becomes tiring, and good posture requires constant vigilance. One funny Web video later, and you’ll be slouching into your computer screen.

The first piece of advice for long-term sitters is to take frequent breaks. (You can find some simple stretches and exercises you can do without leaving your desk at http://backandneck.about.com/od/exercise/ig/Stretch-at-Your- Desk.) The second piece of advice is to conduct regular “posture checks.” With each posture check, your goal is to review what you’re doing and pull your body back into line. The most common mistakes include pushing out your stomach (which curves and overextends your back), hunching your shoulders, and craning your neck. To make sure you’re sitting pretty, use the picture on this page as a quick posture checklist.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

With all our experience sitting, it’s a bit disappointing to learn that most of us aren’t very good at it. Proper sitting is surprisingly hard work, especially when you add computers, telephones, and office work into the mix. Part of the problem is that sitting “at the ready” quickly becomes tiring, and good posture requires constant vigilance. One funny Web video later, and you’ll be slouching into your computer screen.

The first piece of advice for long-term sitters is to take frequent breaks. (You can find some simple stretches and exercises you can do without leaving your desk at http://backandneck.about.com/od/exercise/ig/Stretch-at-Your- Desk.) The second piece of advice is to conduct regular “posture checks.” With each posture check, your goal is to review what you’re doing and pull your body back into line. The most common mistakes include pushing out your stomach (which curves and overextends your back), hunching your shoulders, and craning your neck. To make sure you’re sitting pretty, use the picture on this page as a quick posture checklist.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Thursday, July 8, 2010

Standing posture

Standing is a seemingly simple activity that the human body doesn’t do very well. Our bodies are designed to handle much more ambitious activities (climbing hills, hunting elk, and so on). Keep us stuck in one place, and we suffer—our backs ache, our posture slips, and we end up with more spinal distress than a performer in Cirque du Soleil.

During short periods of standing, you can reduce strain by avoiding the worst mistakes. Keep your head, shoulders, and feet lined up (imagine a straight line that links the top of your head to the middle of your feet). The biggest backaches start when you pull your head forward or lean your upper body backward.

If you must stand for a long time, shift your weight from one foot to the other or rock your feet from heel to toe. Putting one foot on a very low rail, like the sort you find at some bars, can also reduce the pressure on your back. Posture experts say leaning is acceptable, but only if you put your lower back, shoulders, and the back of your head against a wall—a position that might draw a few curious stares.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

During short periods of standing, you can reduce strain by avoiding the worst mistakes. Keep your head, shoulders, and feet lined up (imagine a straight line that links the top of your head to the middle of your feet). The biggest backaches start when you pull your head forward or lean your upper body backward.

If you must stand for a long time, shift your weight from one foot to the other or rock your feet from heel to toe. Putting one foot on a very low rail, like the sort you find at some bars, can also reduce the pressure on your back. Posture experts say leaning is acceptable, but only if you put your lower back, shoulders, and the back of your head against a wall—a position that might draw a few curious stares.

Source of Information : Oreilly - Your Body Missing Manual

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Posture and Pain

Your back puts up with a great many indignities. Ordinarily, your spine adopts three natural curves that help distribute your body’s weight. They go by the names cervical, thoracic, and lumbar curves.

No matter how good your posture, when you stay in a single position for a long time (for example, when you stand in line, sit at a desk, or drive across the country), you put increased pressure on parts of your spine, and you usually end up flattening or excessively curving these parts of your back. Your muscles strain to compensate, causing problems that range from a stiff neck to an aching lower back.

There’s no ironclad defense against back problems. However, you can do a lot by observing good posture, practicing backstrengthening exercises, and avoiding back-straining experiences.